|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Occult Surrealist: Ithell Colquhoun and automatism Richard Shillitoe describes the links between Occult practices and Surrealism, particularly with regard to the work of Ithell Colquhoun. During her lifetime Colquhoun 1906 - 1988 was probably this countries foremost artist-occultist. She lived in Cornwall from 1948 and is one of the artists included in Tate St Ives' The Dark Monarch.

Introduction

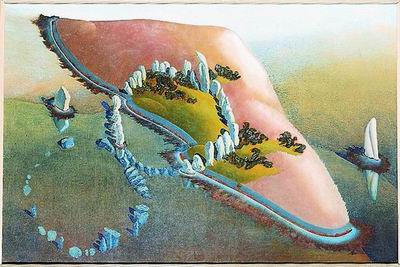

Following this visit she began to make extensive use of automatic techniques herself. This change in her practice was as much philosophical as it was technical. Rather than being pre-planned and premeditated, her art became more spontaneous, making use of chance effects and random processes. From smooth surfaces from which all traces of brushstrokes were minimised, textural features, blots, smudges and stains now became an integral part of her work.

Automatism and surrealism In the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924) surrealism was defined in terms of automatism: SURREALISM: pure psychic automatism, by which an attempt is made to express, either verbally, in writing or in any other manner, the true functioning of thought. The dictation of thought, in the absence of all control by reason, excluding any aesthetic or moral preoccupation. (2)

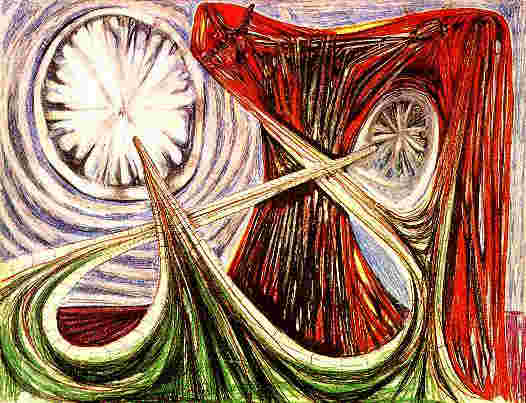

Because of these innovations, by the time Colquhoun came to surrealism, the search for a pictorial equivalent of automatic writing had ceased to be a central concern. Indeed, by the time of the Second Manifesto (1930) automatism was hardly mentioned at all: the debate had moved on to focus upon what Breton described as ‘the occultation of surrealism’ in the search for that certain point in the mind at which opposites cease to be perceived as contradictory. (3) Whilst some artists emphasised automatism’s role in discovering hidden aspects of the artist’s psyche, others, such as Roberto Matta, valued it as a means for uncovering hidden aspects of objects and for the exploration of what lies beyond the confines of the visible world. Its optical image is just one aspect of the existence of an object. Galaxies, crystals and living matter go through processes of creation, existence and destruction. They exist in time, change with the passage of time and can be observed from multiple perspectives. Conventionally, however, they are only depicted at a fixed point in their history, from a single point in space and, inevitably, with a palette limited to colours which reflect light of a visible wavelength.

Breton, too, understood the mystical nature of the theory and the way it could break down all barriers of time and place: ‘It contains fusion and germination, balances and departures, it incorporates an understanding between cloud and star, we can see all the way back and all the way down… the image of the universal sperm circulates through it.’ (6)

Automatism and psychopathology For most artists automatism was a two-stage process: the production of the initial marks using some method that relied on chance, followed by their modification, interpretation and elaboration, using a more conscious and controlled technical process.

Colquhoun understood that for an artist to use automatic processes was akin to a patient generating his or her own Rorschach cards and, by interpreting them, she (and, by implication, viewers) would gain access to the hidden contents of her unconscious(9). This was not done with therapeutic intent, as was the case with two other members of the British surrealist group, Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff (picture left) who, in the course of their extraordinary collaboration produced a large number of works laden with psychoanalytic symbols that ooze infantile sexuality and that were painted with the express purpose of being subjected to analytic scrutiny(10). Pailthorpe and Mednikoff were working within an established medical psychology tradition, dating back to 1889 when the French psychiatrist Pierre Janet first advocated the therapeutic use of automatism(11). In contrast, Colquhoun’s aim was not to banish symptoms and become better adjusted. She was a trained artist with considerable technical ability who expected her works to be displayed in galleries. She expected it to be sold and to be hung on walls, not analysed and filed in a therapists’ case notes.

Automatism and the occult

For Colquhoun, automatism was not simply the adoption of a state of mind which suspended conscious control. Whilst disconnecting herself from her conscious self, she was also connecting herself with a larger whole. In choosing the word ‘mantic’ to describe automatic methods, Colquhoun was deliberately using a word which, derived from ancient Greek, refers to a process of divination arising from divine possession. Colquhoun aimed to lay herself open to internal, unconscious, forces as well as external spiritual ones. Inspiration could come from any source, internal or external. All that was necessary was some degree of dissociation in the operator, although, for her, ‘this seldom reaches the stage of trance’. (13) In automatism, the act itself, not just the resulting image, is significant, just as the way in which a magical ritual is performed significantly influences the outcome.

Although she was dismissive of the cosy

platitudes usually produced by spiritualist mediums, Colquhoun certainly

regarded their approach as capable of revealing great discoveries. She

cited the work of the

One of the reasons why automatism became central to Colquhoun’s work was because it provided her with methods that, to her mind, linked the surreal with the hermetic both philosophically and technically. For example, in arguing the point that the forms created by automatic methods are closely dependent upon the unconscious mood of the operator, she drew a parallel with the alchemist who sees, in his retort, the contents of his own subliminal fantasy. Similarly, just as the apparently random pattern of tea-leaves in a cup may suggest the shape of the future, so, too, an ink blot or stain may possess divinatory powers. In elaborating this, she drew clear parallels between alchemical transformation and automatism, suggesting that the four traditional elements of alchemy each have corresponding automatic methods. Fire can be related to fumage, water to écrémage and parsemage and earth to decalcomania. Air can be related to techniques where powdered materials are blown or fanned and allowed to settle on the artist’s surface. (16) Whilst some surrealist artists emphasised automatism’s role in discovering hidden aspects of the artist’s psyche, others, such as Roberto Matta, valued it as a means for uncovering hidden aspects of objects; to explore what lies beyond the confines of the visible world and within other worlds and other dimensions. The optical image is just one aspect of the existence of an object. Galaxies, crystals and living matter go through processes of creation, existence and destruction. They exist in time, change with the passage of time and can be observed from multiple perspectives. Conventionally, however, they are only depicted at a fixed point in their history, from a single point in space and, inevitably, with a palette limited to colours which reflect light of a visible wavelength. To his attempts to use automatism to give form to those things which cannot be seen except as an inner vision, Matta gave the name psychological morphology, a phrase Colquhoun used to describe her paintings of the 1940s. The act of painting, therefore, became an act of divination that connects the artist to natural and spiritual forces. Automatism and the occult represent linked routes to spiritual self-development.

For more on Colquhoun visit www.ithellcolquhoun.co.uk Richard Shillitoe wrote a short biography of Ithell Colquhoun for artcornwall.org in 2006 http://www.artcornwall.org/profile%20ithell%20colquhoun.htm and is author of Ithell Colquhoun: Magician born of Nature http://www.lulu.com/product/paperback/ithell-colquhoun-magician-born-of-nature/5092185

Notes 1. Hiekisch-Picard, S. 2006. Gordon Onslow Ford the Formative Years: Paintings from the 1930s and 1940s. San Francisco: Weinstein Gallery. 2. Breton, A. First Manifesto of Surrealism. Published in English translation in Seaver, R. and Lane, H.R. Manifestos of Surrealism, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1967. 3. Breton, A., Second Surrealist Manifesto. Available in English in Seaver and Lane, op cit. 4. Onslow Ford, G. 1940. The Painter looks within himself. The London Bulletin, issues 18-20. 5. Breton, A. Surrealism and Painting. Translated by Simon Watson Taylor, Harper and Row, New York, 1972 pp 183-188. 6. Colquhoun, I. 1976. Exhibition catalogue: Ithell Colquhoun: Surrealism, Paintings, Drawings, Collages 1936-76. Penzance: Newlyn-Orion Galleries. Introductory essay. 7. Colquhoun, I. The Mantic Stain. Enquiry, 2, No. 4 (October-November) 1949. pp. 15-21. and Colquhoun, I. Children of the Mantic Stain. Athene, May 1952, pp.29-34. 8. Herman Rorschach always stated that his test measured the perceptive power of the subject, and was not a projective measure of the unconscious, although this is how it has come to be used. The test has the dubious distinction of being, simultaneously, the most cherished and the most reviled of all psychometric tests. See Hunsley, J. & Bailey J.M. 1999, The Clinical Utility of the Rorschach. Psychological Assessment vol.11, pp. 266-77. 9. Colquhoun, I. Children of the Mantic Stain, op cit. 10. For details of this collaboration and for criticisms of the venture from the viewpoints of surrealism and psychoanalysis, see Walsh, N. (ed) Sluice Gates of the Mind. The Collaborative Work of Pailthorpe and Mednikoff. Leeds Museums and Art Galleries, 1998. 11. Janet was the source of Breton’s ideas about automatism. See Balakian, A. André Breton: Magus of Surrealism. Oxford University Press, New York, 1971. 12. see Choucha, N. Surrealism and the Occult. Mandrake, Oxford, 1991. 13. Colquhoun, I. Notes on Automatism. Melmoth No. 2 1980. pp. 31-32. 14. Colquhoun, I. Notes on Automatism, op cit. The role of automatic writing in the discovery of the Edgar Chapel at Glastonbury Abbey is described in Bligh Bond, J. The Gate of Remembrance. Blackwell, Oxford, 1918. 15. Yeats, W.B. A Vision. Macmillan, London, 1937. 16. Colquhoun, I. Children of the Mantic Stain. Athene, May 1952, pp. 29-34.

|

|

|

In the summer of 1939 the painter Ithell

Colquhoun paid a visit to André Breton in Paris, before going on to Chemillieu

where she met Roberto Matta (picture right) and Gordon Onslow Ford (1). Both these

artists were experimenting with automatic methods of painting to find

images from within the unconscious which could then be developed or

interpreted, if desired, through more conscious means.

In the summer of 1939 the painter Ithell

Colquhoun paid a visit to André Breton in Paris, before going on to Chemillieu

where she met Roberto Matta (picture right) and Gordon Onslow Ford (1). Both these

artists were experimenting with automatic methods of painting to find

images from within the unconscious which could then be developed or

interpreted, if desired, through more conscious means.

To his attempts to use automatism to give

form to those things which cannot be seen except as an inner vision,

Matta gave the name ‘psychological morphology’, a phrase Colquhoun used

to describe her paintings of the 1940s. For the painters involved in

this theorising – primarily Matta, Esteban Frances and Gordon

Onslow-Ford – the possibilities were, literally, endless; ‘It is a

Hell-Paradise where all is possible’ wrote Onslow-Ford. He continued;

‘The details of the farthest star can be as apparent as those of your

hand. Objects can be extended in time so that the metamorphosis from

caterpillar to butterfly can be observed at a glance.’ (4)

To his attempts to use automatism to give

form to those things which cannot be seen except as an inner vision,

Matta gave the name ‘psychological morphology’, a phrase Colquhoun used

to describe her paintings of the 1940s. For the painters involved in

this theorising – primarily Matta, Esteban Frances and Gordon

Onslow-Ford – the possibilities were, literally, endless; ‘It is a

Hell-Paradise where all is possible’ wrote Onslow-Ford. He continued;

‘The details of the farthest star can be as apparent as those of your

hand. Objects can be extended in time so that the metamorphosis from

caterpillar to butterfly can be observed at a glance.’ (4)_-_1937.jpg) The

word that best describes the second stage, the imaginative

interpretation of the initial stimulus, is that it is an act of

projection. Projection is a word that is frequently used in contexts

such as alchemy and analytic psychology. Colquhoun was well aware of

both these usages. In two articles, The Mantic Stain (1949) and

Children of the Mantic Stain (1952) (7) she referred to the

classic projective test of the psychoanalysts – the Rorschach ink-blot

test. Presented with an ambiguous stimulus, patients project their own

interpretations on the image, and, in so doing, give the therapist

information about their psychopathology that cannot be articulated at a

conscious level. (8)

The

word that best describes the second stage, the imaginative

interpretation of the initial stimulus, is that it is an act of

projection. Projection is a word that is frequently used in contexts

such as alchemy and analytic psychology. Colquhoun was well aware of

both these usages. In two articles, The Mantic Stain (1949) and

Children of the Mantic Stain (1952) (7) she referred to the

classic projective test of the psychoanalysts – the Rorschach ink-blot

test. Presented with an ambiguous stimulus, patients project their own

interpretations on the image, and, in so doing, give the therapist

information about their psychopathology that cannot be articulated at a

conscious level. (8) Automatism

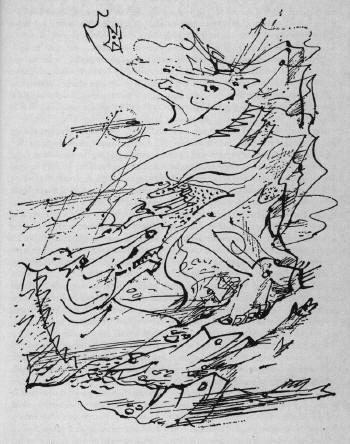

was not invented by the Surrealists. Automatic writing was a

traditional technique used by mediums and spiritualists who would put

themselves into a trance-like state in order to receive dictation from

the spirit world. Additionally, occult researchers such as Austin Spare

in England (picture right) had sometimes experimented with automatic drawing. (12) For

the surrealists receptivity to the internal unconscious was the

motivating factor. For occultists, the driving force was access to the

external spirit world.

Automatism

was not invented by the Surrealists. Automatic writing was a

traditional technique used by mediums and spiritualists who would put

themselves into a trance-like state in order to receive dictation from

the spirit world. Additionally, occult researchers such as Austin Spare

in England (picture right) had sometimes experimented with automatic drawing. (12) For

the surrealists receptivity to the internal unconscious was the

motivating factor. For occultists, the driving force was access to the

external spirit world. Elizabethan alchemist, Dr John Dee and his partner

Edward Kelly as one example, and the archaeologist F. Bligh Bond and his

scribe John Alleyne as another. Dee and Kelly had, reportedly,

discovered the Enochian system of magic through mediumistic activities,

whilst Bligh Bond’s discovery of the Edgar Chapel at Glastonbury Abbey

through automatic writing had been a cause celebre in 1918. (14) She was

also well aware that the poet W.B. Yeats, who was also a significant

figure in the occult world, had made extensive experiments in automatic

writing with his wife that resulted in his metaphysical book A Vision.

(15)

Elizabethan alchemist, Dr John Dee and his partner

Edward Kelly as one example, and the archaeologist F. Bligh Bond and his

scribe John Alleyne as another. Dee and Kelly had, reportedly,

discovered the Enochian system of magic through mediumistic activities,

whilst Bligh Bond’s discovery of the Edgar Chapel at Glastonbury Abbey

through automatic writing had been a cause celebre in 1918. (14) She was

also well aware that the poet W.B. Yeats, who was also a significant

figure in the occult world, had made extensive experiments in automatic

writing with his wife that resulted in his metaphysical book A Vision.

(15)